A Quantum Experience of Inauguration Day

On New Orleans' resistance, culture bearing, and cultural transference

I had a joyful Inauguration Day, until I turned on MSNBC.

Both self-states were true. The day was joyful, and it was horrific. It was a matter of both/and not either-or. I had a joyful day marking the damage that Lady Liberty had suffered and celebrating the promise of her renewal. Trump poured forth a chaos of words in his acceptance speech (more “American carnage” with a heady dose of threats), followed by signing dozens of Executive Orders.

He pardoned over 1500 insurrectionists. Foreign nations “empty their prisons to send us their criminals”—Trump’s typical projection. Back in power, he makes his projection real. Soon they will form Trump’s Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary storm troopers that will do his will extrajudicialy, as they did on January 6th. Will they don brown shirts? We’ll see.

It was a yin-yang kind of day. Light and dark were both true. In the light dark emerged, in the dark light emerged.

In quantum physics light is a particle if you perform one experiment, a wave if you perform another. It all depends how you look at it. Every moment of every day is a quantum experiment: how will I frame it?

I had a particle-wave kind of day. The challenge was to embrace the reality of both frames.

Of course, the terrors of Trump’s executive decrees are real and unrelenting. He's flooding the zone, sending eight pass receivers against our meager defenses. The effect is to freeze out our sense of agency: what can we do?

And yet there I was doing something, gathering New Orleanians to perform what is becoming something of a ritual: a counter-inaugural event at the stroke of noon Eastern time, just as Trump was taking the oath of office. We did it eight years ago. At both counter-inaugurals Doctor Brice Miller and the Mahogony Brass Band played a dirge as we reviewed the damage Lady Liberty had suffered. Then as we took some care of Lady Liberty in her coffin, the band played the traditional upbeat Glory Glory, Since I've Laid My Burdens Down, a song that remembers the joy of a life well lived, and suggests that she will be reborn among the Saints as they go marching in.

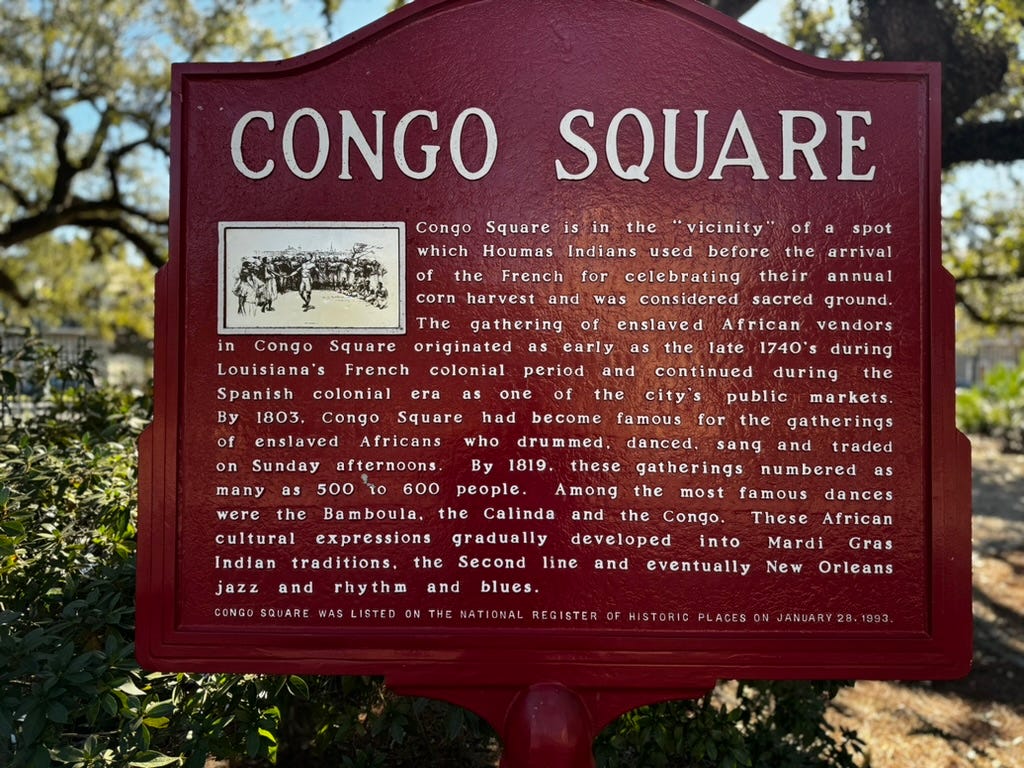

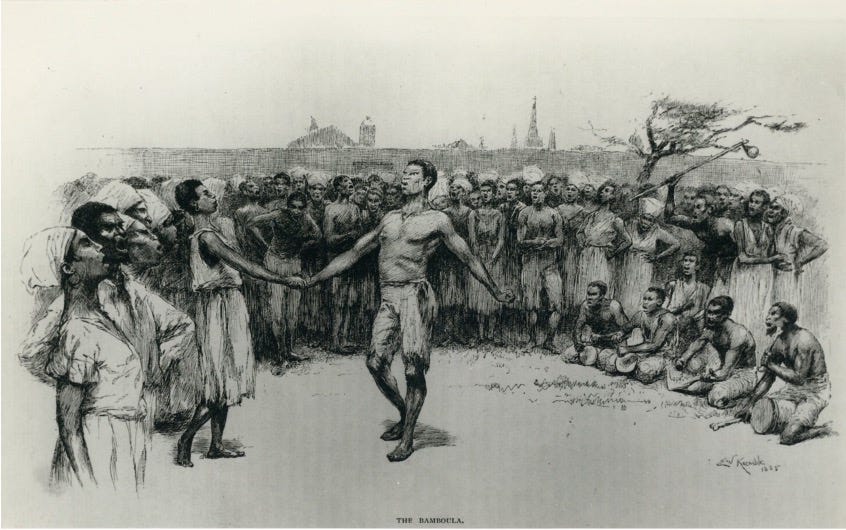

We gathered at Congo Square where it can be said the first freedoms for Black Americans emerged. There in drum circles remembered from before the Middle Passage, enslaved New Orleanians were allowed by the Code Noir of French colonials—and the Coda Negra of the Spanish who ruled after 1763—to play their traditional drums. Other colonies feared drums would be used to foment rebellion., In New Orleans, instead, they drummed and danced and chanted the Bamboula rhythms that became the foundation of the syncopated, clavé polyrhythms from which jazz emerged—a shout of rebellion mixed with joy. According to the great saxophonist Sidney Bechet, the music was born from their longing for “a place where they all used to be happy once”—that is, before crossing the ocean chained in the hold of slave ships. Building community, the music’s call and response, it’s Yes, and… structure gave voice to both our individuality and our shared humanity.

Congo Square is situated beneath exalted Live Oaks in Louis Armstrong Park, named for one of the great champions both of improvisation and of freedom. Louis invented the jazz solo. His meticulously prepared art changed American and world culture, perhaps the greatest gift an enslaved people has ever given to their enslavers. Other than their lives and toil, though those weren’t gifts, they were stolen.

Louis himself was a bit beat up by the Be-Bop crowd when they Uncle Tom’d him. Miles Davis once said:

“I always hated the way they [Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie] used to laugh and grin to the audiences. I know why they did it—to make money and because they were entertainers as well as trumpet players. They had families to feed. Plus they both liked acting the clown; it’s just the way Dizzy and Satch were. I don’t have nothing against them doing it if they want to. But I didn’t like it and didn’t have to like it.”

That’s Miles in his role as “angry young man.” It’s Miles as jazz purist. Miles had so little room for entertainment that he often performed with his back to the audience.

Miles was to change his tune. In 1957 Governor Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to bar the door against nine Black students attempting to integrate Central High School. In Grand Forks, ND, an intrepid young college senior named Larry Lubenow, moonlighting at the Grand Forks Herald picked up an assignment to talk to Louis Armstrong “about music.” In the green room he asked one music-related question, he reported to NPR, then “I asked Louis if he knew that he was staying in the hometown of Judge Ronald Davies who made the decision at the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals on Little Rock.”

“And he said he didn't. Then he went off.” A number of on-air unquotables streamed from the lips that had confected “West End Blues” and invented scat singing during the recording of “Heebie Jeebies.” Louis challenged not only Faubus but President Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

Since it was the news of the Judge Davies’ birthplace that set Louis off, and since the 5th Circuit is headquartered in New Orleans, Louis’s hometown, it’s worth noting that the 5th Appellate Court is now once again known as one of the most extreme, conservative courts in the land. Yet , led by great progressive jurists like Skelly Wright and John Minor Wisdom, the court later became known for a series of crucial decisions that advanced the goals of the Civil Rights Movement. Wisdom received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1993.

In 2007, the 50th anniversary of his article, Lubenow conversed with Scott Simon on NPR:

SIMON: He had some strong words for people in the U.S. government then, didn't he?

MR. LUBENOW: Well, even stronger than that which was printed. He used expletives when he talked about Ike and John Foster Dulles and also Orval Faubus.

SIMON: What did he call Governor Faubus?

MR. LUBENOW: Well, I can't repeat it, not on NPR. It's...

SIMON: I thought it was just an ignorant plowboy. You can repeat that.

MR. LUBENOW: Well, that's what we went with, and Louis said, fine, go with it.

SIMON: So let me get this straight. He didn't actually say ignorant plowboy. He said something else and you said, let's see if we can agree on...

MR. LUBENOW: Yes.

SIMON: ...an epithet here.

MR. LUBENOW: He said he's a no-good mother.

SIMON: And he probably didn't mean mother. I see what you mean.

MR. LUBENOW: No.

SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER

The student-journalist got $3.50 for the story. He later became an advertising executive in Austin, TX. He died in 2014.

Louis’s expurgated words made headlines across the world. Embarrassed, Ike order the 101st Airborne into Little Rock. History changed because of Pops’ words, and because of the agency of a college senior who made his way to that North Dakota green room with an assignment to talk about music.

It still hasn’t changed enough but at least Miles did. He later stated: "You can tell the history of jazz in four words: Louis Armstrong. Charlie Parker."

Louis himself is an example of quantum experience. His work is pure entertainment and pure jazz. If it’s at all tainted by minstrelsy,[1] it is also—both/and—art as pure as any that has poured forth from the Hippocrene, the spring on Mount Helicon where the Muses were said to live.

Suffice to say, just a few yards from Congo Square, we celebrated Lady Liberty on holy ground—Louis Armstrong Park.

The Joy

I don’t need to recount Trump’s terrors.

I’ll focus on the little joys that made my day magical.

Lady Liberty had seen better days. Tattered, her arm in a sling, her bright flame brought low. The years had done her the kind of bad the blues are born of. The edges of Hurricane Milton had tattered and torn her papier mâché. She needed a paint job. So did what she stood for, only more so.

As luck would have it—and luck proverbially comes to the prepared—my partner L.J. Goldstein, Prince of New Orleans Street Theater, had brought a can of copper paint for the undercoating as well as the original gallon of paint the color of verdigris Lady Liberty is known for. Armed with brushes L.J. had acquired, the crowd gathered to give Lady Liberty a new coat.

My favorite participants were a lovely French couple who danced with their toddler to Mahogony Jazz Band’s syncopated rhythms. Then, fellow countrymen of those who first donated Lady Liberty, they picked up a brush.

I didn’t get their last names, but the mother was Zoë—which means life. And their daughter was named for one of the greatest Rock ‘n Roll songs of all time: Eric Clapton’s “Layla.” That’s what Lady Liberty needs: a little bit of Rock ‘n Roll, and a lot of renewed life—zoë—which was what Rock ‘n Roll was always about anyway.

These synchronicities recalled for me Milan Kundera’s lovely phrase: “If a love is to be unforgettable, fortuities must immediately start fluttering down to it like birds to Francis of Assisi’s shoulder.” That day they fluttered.

These acts of renewal were echoed when after our event we joined the Martin Luther King, Jr. remembrance that took place nearby, beneath the Live Oaks in the drum circle of Congo Square. Aptly, it began with drumming, as it did in Congo Square’s Bamboula circles long past.

In this modern moment beneath the Live Oaks an elder drummer, Mr. Collins, was joined by a young white man at his drum. They played a polyrhythmic beat that repeated again and again, the kind of trance-inducing music that survived the Middle Passage.

At one point the elder picked up a guiro, the African scraping instrument that survives today in Zydeco frottoirs, or rub boards. The instrument caught a young boy’s eye and he approached the elder. I watched as a certain gleam—call it the gleam of culture-bearing—entered the elder’s eye. He saw the opportunity before him. He demonstrated the use of the guiro and the rhythm called for, then handed it to the boy. To my amazement—I admit I have no musical background—the kid had it from the get-go. The elder returned to his drums.

What I had witnessed was an act of culture bearing and cultural transference. It’s what the Treme neighborhood, the first home of Free Blacks in American history, had long been known for. Some attribute to Treme's bars and dance halls the birthplace of jazz. (Personally I think South Rampart—home to Buddy Bolden and Louis Armstrong, the Eagle Salooon and Funky Butt—had at least an equal role). Jelly Roll Morton, and many another first-generation jazz great, hailed from Treme. It's no coincidence that some of the greatest drummers of the R&B era—including Earl Palmer, Smokey Johnson, and James Black—grew up in Treme. The rebirth of the brass band tradition emerged from Treme: Dirty Dozen, Rebirth, Soul Rebels, even Mahogony. Many legendary musical families, the Batistes and the Andrews, come from Treme: think Jon Batiste who is transforming jazz today, wedding it to pop, and Trombone Shorty Andrews who is merging jazz and rock. David Simon’s HBO series Treme was based on post-Katrina New Orleans and featured many musicians from famous Treme families.

Witnessing this cultural transference was a little joyful epiphany. I was there. Something was revealed. (Epiphany comes from Greek epiphainein ‘to reveal’).

The epiphany had duration. Another young Black boy approached Mr. Collins who had returned to his drumming. The same gleam entered the elder’s eye. He demonstrated the not uncomplex rhythm on the drum, and the boy had it at first stroke. The musical gene pool in Treme is deep. I was swimming in it.

Did the terrorism Trump was simultaneously perpetrating negate these events? No, they existed in the same quantum state, both/and, not either-or. The joy was real, caring for Lady Liberty, watching liberty at play, being revived by the improvisations I witnessed.

The way forward for the resistance is such acts of tradition-transference. Breaking traditions, throwing our democratic norms under the bus, is Trump’s bread and butter. Such acts of remembrance and renewal—sourced from the root—will reconstitute the future of democracy—that gumbo of voices and longings—longings for a place we can be happy—if we are to have a democracy we can recognize.

This 3-minute video captures some of the magic of the counter-inaugural:

The next day, as if Nature herself took note of Trump’s deep-freeze terror campaign, New Orleans was socked in by 8 inches of snow, the biggest snowstorm we’ve had in a century.

Liked this post? I’d be grateful if you’d give the ❤️ button a tap! It helps keep me going to know that you’ve read this far and you appreciate my writing.

[1] When he was 8-years old, Louis participated in a talent show at the Iroquois Theater, a Black burlesque hall on South Rampart Street. Just before taking the stage he put his face in a sack of flour. He went on in “white face.” If Louis’s natural wide grin—Satchmo came from an earlier nickname, Satchel Mouth—tainted his entertainment, he had minstrelsy’s number from an early age. Throughout his life when asked how things were going, Pops often answered, “Nothing new, white man's still ahead.”

You live in fantasyland if you believe New Orleans is on the right track. This city has been going down since the first Landrieu decided that color surpass merit.

Wonderful garden tending! Keep the ideas and connections blooming!