If a love is to be unforgettable, fortuities must immediately start fluttering down to it like birds to Francis of Assisi’s shoulder.

— Milan Kundera

Conceptual and environmental artist Dawn DeDeaux’s Free Fall is a “concrete poem” of erasure and of mourning. Free Fall is also a call to action.

In Free Fall, Puritan poet John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost intersects with the environmental erasures suffered for over a century by the state that, on its license plate, still proclaims itself Sportsman’s Paradise.

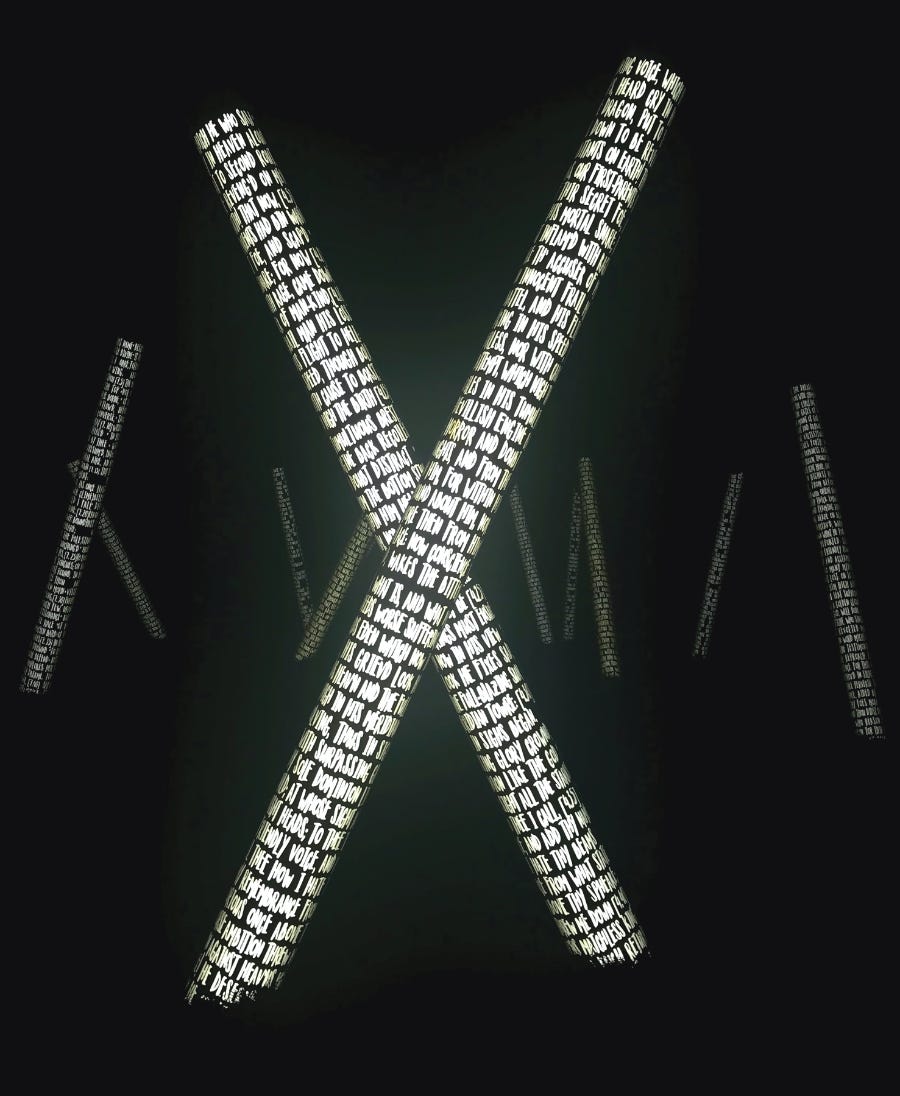

Free Fall was installed on the “neutral ground” (or median) along five blocks of New Orleans’ Poydras St., the main artery of the city’s central business district. It stood for nearly two years smack dab before the Superdome, home to the New Orleans Saints and the once infamous shelter to survivors of Katrina's floods.

Free Fall was taken down in the fall of 2024 so that increased security measures could be installed before the February 2025 Super Bowl, measures which the domestic terrorism attack on Bourbon Street on New Year’s Eve made prescient.

On this at once heroic and tragic ground, excerpts from Paradise Lost were affixed to “falling” concrete columns, a stunning literalizing of “concrete poetry,” a tradition that flourished in antiquity, again in Milton’s day, and once again in the 20th century.

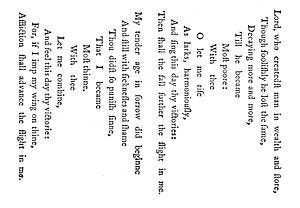

In Milton’s era the Anglican divine George Herbert wrote concrete poems such as “The Altar”—a prayerful poem arranged on the page to look like an altar—and “Easter Wings” (1633), printed sideways on facing pages so that the lines would call to mind angels’ outstretched wings:

DeDeaux drags this tradition into public space three-dimensionally—casting Milton’s poem in real concrete! DeDeaux at once renews and enlarges the tradition. In this prophetic work DeDeaux presents herself as a stand-in for Milton’s archangel Gabriel. After the fall from Eden, the archangel, speaking to Adam, foretells man’s coming redemption through Christ—and the Apocalypse that will one day end it all. For Milton, controversially in his day, Christ’s coming and the end times made Adam and Eve’s tasting the apple a “fortunate fall” (felix culpa). That happy fall is an idea far less applicable to the anthropogenic final days we seem to be facing and upon which DeDeaux’s installation comments.

Certain Evangelical Christians happily voted for Donald Trump in 2024 who seems committed to hastening those end times, a free fall indeed.

Speaking in Tongues: DeDeaux’s Quest for a Prophetic Voice

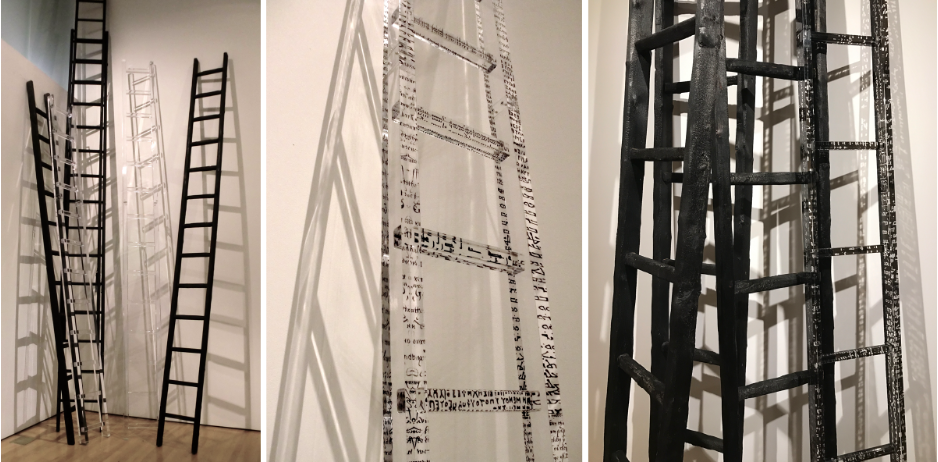

This is not DeDeaux’s first foray into concrete poetry, nor, for that matter, her first effort at prophecy. In a series titled Speaking in Tongues she was drawn to the similarities among early apocalyptic narratives about the “end of time.” DeDeaux used glass ladders as vessels for her abstracted versions of the earliest known written scripts.

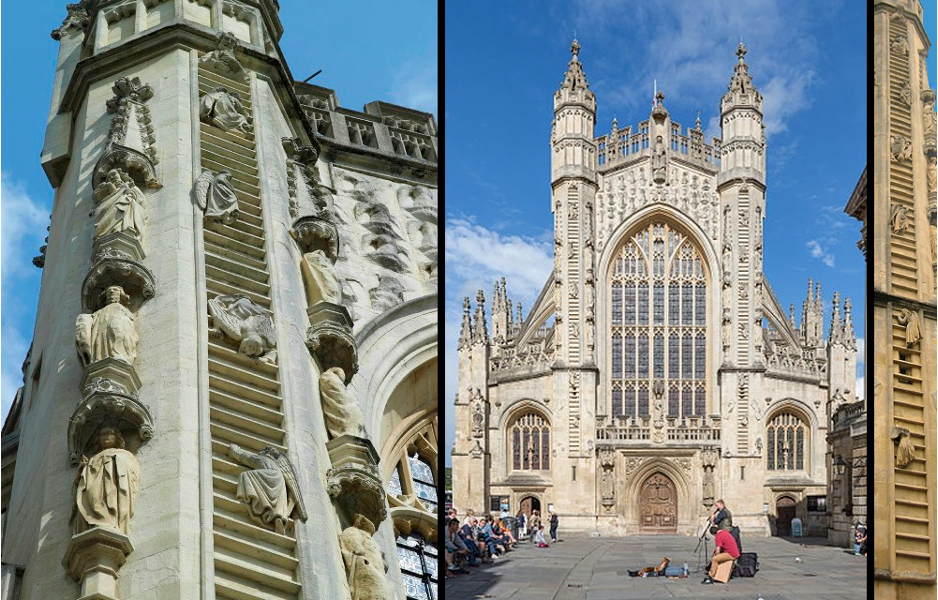

Both reference the ancient symbolism that suggests that as one ascends the rungs to be nearer god one “sees into the future.” Jacob climbs a ladder as he wrestles God’s angel. Jacob’s ladder was delightfully reimagined by the 15thcentury stonemasons of Bath Abbey, positioned on the west face, traditionally associated with the Apocalypse. The square before the west façade was known as le paradis, which in Christian theology the Apocalypse returns mankind to. DeDeaux, like the epic poet, is familiar with Christian eschatology.

Now, in Free Fall, DeDeaux returns to text.

Excerpting Paradise Lost on concrete columns using highway reflective tape, her project can also fruitfully be compared to poet Ronald Johnson’s erasure poem Radi Os. Johnson, whom Guy Davenport once called America’s greatest living poet, rewrote the first four books of Milton's poem by erasing, producing a new text in which the few remaining words float in the white page space left by the absented words. Milton’s title Paradise Lost becomes Johnson’s Radi Os.

The majestic 122 words of Milton’s first sentence,

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing heavenly muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed,

In the beginning how the heavens and earth

Rose out of chaos: Or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa's brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God; I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventurous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above the Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.

becomes merely 13 words which, in startlingly modern voice captures, Milton’s epic purpose:

Where Johnson’s Miltonic remainder is set off by white space, DeDeaux employs highway night-reflective vinyl. The vinyl tape reifies and literalizes Milton’s famous description of hell through fallen Lucifer’s eyes, to reveal its“darkness visible”: at night, passing cars (or your iPhone flashlight) make the otherwise-unseen words glow. Free Fall is both literally and figuratively a prophetic reflection on our coming ecological collapse.

In a disconcerting synchronicity —what Milan Kundera calls “fortuities that flutter down like birds to Francis of Assisi’s shoulder”—Johnson considered Radi Os to be a section of his long poem Ark, just as DeDeaux considers Free Fall to be part of her ongoing visionary “post-earth” MotherShip Series in which a zeppelin-like airship serves as mankind’s ark to find a new planetary paradise. Too, Radi Os was reprinted in 2005 by Flood Editions just as DeDeaux’s Free Fall emerged after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the great deluge that followed the federal levees’ failure. Both her projects—Mothership and Free Fall—were conceived without DeDeaux’s knowledge of Johnson’s work or career. Disconcerting synchronicities abound, fluttering down upon DeDeaux and her audience.

The Vanishing Mississippi Delta

DeDeaux’s concept-rich artistic projects have long been disconcerting. Free Fall with its toppling columns and partly-erased epic poem reminds us of what she calls “this literal ‘vanishment’ of place … due in large part to the short-sightedness of industry and politics, all supported by the products we individually buy and the people we individually elect.”

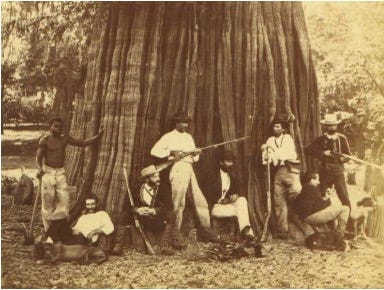

Built over millennia by spring inundations, the Mississippi River Delta began its vanishment in the 19th century when the Army Corps of Engineers’ levee-raising began to starve the delta of the sediments that annually rebuild it. Then, in the early 20th century, the delta’s first growth cypress swamps were clear-cut. The discovery of oil brought pipeline canal-digging to the delta, which brought saltwater intrusion, which killed the native oyster reefs and the marsh. The three—cypress, oyster beds, and marsh—had helped build and hold the delta together over millennia. When the three dominoes fell, the delta began to vanish. Wetlands the size of Delaware have washed away.

After the delta, is New Orleans next?

Such an apocalyptic question is not idle. For, as environmental writer Christopher Hallowell points out, the delta “serves as breeding ground, nursery, food source, and buffer.” With 40 percent of America’s wetlands, Southern Louisiana produces twenty percent of America’s seafood. That’s one thing we’re losing. New Orleans might become another. Hallowell’s “buffer” refers to the truth that New Orleans’ longevity hinges on these delta wetlands. According to scientists, every two and a half miles of wetlands reduces a hurricane’s storm surge by a foot.

At the last-minute Hurricane Katrina swerved toward the state of Mississippi. It was a direct hit from the Gulf. On the Mississippi coast there is no marshland to buffer it. The storm surge was thirty feet and the devastation was, well, apocalyptic. The weekend of Katrina, Ruth’s Chris Steak House had just opened on the second floor of the Biloxi Hard Rock Café. The next morning they found a barge filling the dining room 20 feet above the beach.

On the coast, Katrina, a Category 5 hurricane, was a natural disaster. In New Orleans where Katrina winds were Category 1 or 2, the hurricane was a man-made disaster, the result of ill-constructed federal levees. Meant to keep out rising water, the federal levees were not overtopped. They simply failed. A flood the size of seven Manhattans stood for 5 weeks in the homes and streets of the city.

In “Can We Save New Orleans?” Tulane environmental law professor Oliver Houck confirms that “The coastal marshes act just like a levee, only a flat one. They knock down storm surges, and over the eighty-some miles between New Orleans and the Gulf that amounts to the height of a tall man, six feet or more. That’s a lot of free levee. All we had to do was nurture it and leave it alone. Instead of course, we starved the marshes from the main river and then started cutting them up with canals.” The loss of those “free levees” is another man-made catastrophe waiting to happen.

The math is, yes, disconcerting. The next Category 5 hurricane to hit the city squarely will make DeDeaux’s Free Fall, if not the Superdome itself, look like the next ruins of Atlantis.

Think of fellow artistic prophet Mel Chin’s powerful 2018 Time Square augmented reality installation, Wake and Unmoored, which virtually showed boats cruising above visitors in an imagined future awash in melted icecaps.

So, one day our beloved New Orleans, the soul of America.

Paradise Found

To gauge the delta’s vanishment, consider the letters written home by Sister Marie Hachard (1704-60), an abbess in the first contingent of Ursulines nuns who traveled in 1727 to New Orleans. Just three centuries ago, a decade after Bienville’s founding of New Orleans and six decades after Milton’s epic, Sister Marie described in letters home in lush terms her weeklong journey by pirogue (dugout canoe) from the river’s mouth against the current up to New Orleans:

There are no lands cultivated the whole length of the river, only great wild forests inhabited solely by beasts of all colors, serpents, adders, scorpions, crocodiles, vipers, toads, and others which did us no harm even though they came quite near us….

Paradise found: if in Adam’s Eden lambs lie down with lions, here nuns seem to lie down with crocodiles. Her next letter describes the delta as a cornucopia worthy of Milton’s Eden. Sister Marie displays an reverence for foodstuffs perhaps only the French (or a Louisianian) can bring to table:

Hunting is done about ten leagues from our city and lasts all winter which here begins in October. Many wild oxen are taken and brought here to New Orleans and nearby areas. We buy this meat for three sols a pound, the same as deer, which is better than the beef and mutton you eat in Rouen…. Wild ducks are very cheap. Teal, water-hen [poules-d’eau], geese and other fowl and game are also very common…. Really, it is a charming country all winter and in summer the fish are plentiful and good. There are oysters and carps of prodigioucs size and delicious flavor. As for the other fish, there are none in France like them. They are large monster fish that are fairly good. We also eat watermelons and French melons and sweet potatoes which are large roots that are cooked in the coals like chestnuts….

In my family’s retelling, the delta’s skies were once blackened by flocks of migrating waterfowl attracted from Canada and all along the Mississippi flyway by the delta’s fecund bayous and ponds. According to journalist Rowan Jacobsen, “one fifth of all the ducks in America overwinter in the Louisiana wetlands.”

My great uncle Martin Hingle of Home Place told of bagging nine ducks with one shot. Shotgun shells were an expensive item during the depression so, unsportingly, Uncle Martin waited till a flock lighted on the water. There were stew pots to fill and rice and indigo harvesters to nourish. Now the toes of the Louisiana boot, once the flocks’ destination, are gone, vanished, erased. Can a boot stand without toes? Will the Île d’Orleans—a name early settlers cooked up as a marketing ploy—one day literally be an island?

Paradis Perdu

DeDeaux, too, has deep roots in Louisiana soil. Her grandmother was born just across from one of DeDeaux’s earlier Free Fall installations in a private sculpture park on the Mississippi River. Grand-mère’s town fittingly—and synchronistically—was called Paradis. Paradis is still pronounced as the French would, not sounding the “s.” Once a long stretch of prosperous farms that inspired its name, Paradis, is now a fallow stretch of highway wedged between the river and Bayou des Allemands, named for the Alsatians who settled it. Des Allemands catfish is rightly famous, a little bit of Sister Marie’s cornucopia that still survives.

DeDeaux’s use of vinyl tape also illuminates the problem, literally—there on the columns—and also, alas, figuratively. DeDeaux’s intersection with Paradise Lost means to evoke the problem of free will which much troubled the Puritan and regicide Milton. It troubles DeDeaux too: “we either succumb to a fatalistic future or courageously commit ourselves to a bold new course.”

But here is the inevitable rub: vinyl tape, a petroleum bi-product, is at least a symbolic part of the problem we face. Lake Charles, Louisiana—west of New Orleans and near the Texas border—leads the nation in the production of vinyl siding, and probably vinyl tape too. Lake Charles is one of the most polluted places in the nation. It is not far from the rice field on the “Mamou prairie” where the first oil well in Louisiana was drilled in 1901. The chemicals that Lake Charles residents breathe from the chlorine plants, along with emissions from oil and petrochemical refineries, include vinyl chloride, benzene, and dioxin, all carcinogens.[1]

The environmental impact of concrete pillars DeDeaux—producing carbon dioxide, damage to topsoil, and runoff—is nothing pretty either, as a laconic Cajun might put it.

In Milton’s telling, Eve’s bite of the apple—"she pluck’d, she ate”—cascades through nature:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her Works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost.

Seeking to wake us, DeDeaux tragically participates in the cascading damage she would awaken us from.

DeDeaux’s call to action, then, also points to the challenge we all face. The vehicle of her metaphor drives her in a minor way to the very depredations and hellish future she challenges us to evade at all costs.

DeDeaux certainly does not defend the vinyl and concrete industries. She explains, “one must fight fire with fire.” Indeed, central to Milton’s theology is the idea that God’s mysterious way is to bring good out of evil. Out of Archangel Lucifer’s fall, Eve’s temptation; out of Adam and Eve’s fall, Christ’s coming and our redemption: hence, our fortunate fall.

Free Fall’s Super-placement

Free Fall’s seventy columns were installed down one of New Orleans’ major commercial thoroughfares—surrounded by concrete roadways, concrete high-rises, the massive concrete Superdome coliseum, traffic signals, reflective vinyl street signs and applied glow in the dark lane dividers. So, DeDeaux’s material choices speak directly to this urban vernacular landscape that is Free Fall’s setting.

My own family foundation that supports the arts and educational programming was itself funded by the sale of the global steak empire that hasn’t helped the earth much either. Ruth’s Chris’s exquisite corn-fed prime depends on grain that evolution did not intend cattle to eat. Corn-fed cattle produce 20% more methane, a significant greenhouse gas, than grass-fed cattle. Silver Fern Farms in New Zealand calculates that “we’d need to plant at least 292,455,000 trees (living 10 years) to offset the feedlot corn from one year’s worth of American corn-fed beef.” In 2019 methane was two-and-a-half times pre-industrial levels.

None of our efforts—however idealistic—are untainted. Meanwhile we need to reduce our carbon footprint.

Milton’s theology is old school for most of us, but it still carries this fundamental truth, that we are all fallen, all imperfect. There was no need for art in Eden. Art, the quest for perfection in an imperfect world, is one of the reasons our fall is fortunate.

Comes now DeDeaux’s Free Fall to show us the way back.

Free Fall challenges us to deploy our free will to pull our sportsman’s paradise up by its bootstraps—or what’s left of it. The installation mourns not only what’s lost but prepares for the challenges ahead.

Meanwhile DeDeaux readies her Mothership Fleet, imaginatively preparing for what will soon be nine billion cohorts who will leap into her waiting dirigibles to take us to new homelands on some Mount Ararat on some Goldilocks planet in another solar system.

About Dawn DeDeaux

Dawn DeDeaux is a highly regarded American artist born and based in New Orleans. Her work from recent decades are influenced by cataclysmic events such as Hurricane Katrina, the BP Oil Spill, Louisiana’s vanishing coastline and challenges to planetary existence. DeDeaux has been at the forefront of envisioning a post-anthropocene world as part of her ongoing MotherShip Series, recently on view for two years at MassMoCA and at Houston’s Transart Foundation for Art and Anthropology.

DeDeaux has been Artist-in-Residence at the American Academy in Rome and Robert Rauschenberg and Joan Mitchell Foundations, where she contributed works for her 2022 career retrospective at New Orleans Museum of Art titled The Space Between Worlds accompanied by a comprehensive book published by Hatje Cantz, Berlin.

Her future-tense works consider both the micro and macro challenges ranging from pandemics to environmental hazards—inspiring her survivor wardrobe series Space Clowns and other futurist meditations featured in Eva Diaz’s new book After Spaceship Earth by Yale University Press and her related essay on DeDeaux’s work for Aperture Magazine.

Works by DeDeaux are currently on view at Longhouse Reserve Sculpture Garden in East Hampton, NY and at The Shepherd Art Center in Detroit, MI.

[1] See, Blue Vinyl: The World’s First Toxic Comedy, Judith Helfand, director (2002); Mossville: When Great Trees Fall, director, Alex Glustrom (2020); and Arlie Russell Hochshild’s Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (2018).

Liked this post? I’d be grateful if you’d give the ❤️ button a tap! It helps keep me going to know that you’ve read this far and you appreciate my writing.

Randy this is the best thing you’ve ever written. Love of the earth, love of human culture, in a time of tragedy.

Excellent, keep’em coming ,